As the young men gazed at the water, they saw an unexpected sight: a dead body. They commandeered a boat to retrieve what proved to be the remains of Mary Cecilia Rogers. She had disappeared from her home in lower Manhattan a few days earlier and had been the object of an eager search. A particularly beautiful young woman, she had worked in a cigar store on Broadway—a risqué occupation for a young woman in that era—and had had a large number of suitors.

The coroner determined that she had been murdered—rather than merely drowned. Her clothing was torn, her body marked by bruises, and she appeared to have been sexually violated, maybe by more than one person.

The murder became a cause célèbre, taken up with great enthusiasm by the many tabloids of the day. Various suspects were proposed, including a sailor who had been one of her beaux—her bonnet had come loose and been re-secured with a sailor’s knot. Another theory pointed to the gangs that were rampant in the city at that time. Abducting, raping, and killing an attractive young woman might have been just the kind of sport they enjoyed, and a witness reported seeing someone who could have been Mary Rogers crossing the Hudson in a boat with a group of men.

The case was never solved. But much, much earlier than Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, it inspired an important work of crime fiction.

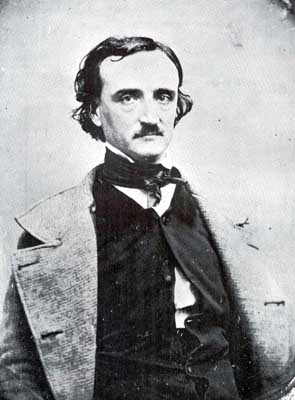

The plot of “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” was completely invented—even fanciful—as anyone who has read it will agree. But the jumping-off point for Dupin’s entry into the case was a fictional article in a fictional Parisian newspaper. Suddenly the New York newspapers were full of articles about a real-life murder—and a sensational one at that. Poe eagerly seized on the Mary Rogers story as a worthy challenge for his sleuth. He would fictionalize the story by transplanting it to Paris—he had already launched Dupin as a Parisian detective—and the story would become “The Mystery of Marie Roget.” Conveniently, Paris even had a river to substitute for the Hudson.

But that’s not all. Since the real-life crime was still unsolved, Poe saw an opportunity for a tour de force. He would solve it.

In pitching the story to the editor of the Ladies Companion, he wrote, “I imagine a series of nearly exact coincidences occurring in Paris . . .” He proposed to analyze the real tragedy through a fictionalized parallel tragedy, to show that Mary Rogers—or Marie Roget—was not killed by a gang, and to reveal who actually did commit the crime. In launching Dupin, Poe had introduced the notion of ratiocination—the exercise of reason (Latin ratio) in the process of analyzing clues.

Everything would have been fine except for one complication. Poe’s story was to appear in three installments. In the first two, he began planting the seeds that would grow and come to fruition when, as he planned, Dupin had his “A-ha!” moment in installment three.

He was incubating his own theory, fastening on the notion that her murderer was a seafaring man, but not the same one that the newspapers favored. Dupin notes that three years earlier she had vanished from home for a few days and later showed up unharmed. He then states, with no foundation in fact, that the typical tour of duty for a merchant seaman is three years. The plan was to reveal that the murderer was a lover of hers, a merchant seaman with whom she had a fling then met up with again when he returned to New York after a three-year tour of duty. The relationship soured and he killed her.

But before installment three appeared, there was actually a breakthrough in the case. The deathbed confession of one Frederica Loss suggested that Mary Rogers had died of a botched abortion and the torn clothing and bruises had been an attempt to draw attention away from the real facts.

Poe, obviously at wit’s end, tried to save himself. “The Mystery of Marie Roget” ends with two densely-written pages of frantic backpedaling in which he basically retracts his earlier statement that the parallels between the Parisian crime and the New York City crime will illuminate the New York City crime. “The very Calculus of Probabilities,” he states, “forbids all idea of the extension of the parallel—forbids it with a positiveness strong and decided just in proportion as this parallel has already been long-drawn and exact.” Say what?

Many historians and Poe scholars have studied the place of the Mary Rogers murder in the history of New York City and Poe’s use of it as inspiration for “The Mystery of Marie Roget.”

Two recent books on the theme are The Beautiful Cigar Girl: Mary Rogers, Edgar Allan Poe, and the Invention of Murder by Daniel Stashower and The Blackest Bird: A Novel of Murder in Nineteenth-Century New York by Joel Rose. Stashower’s book is a fascinating and scholarly treatment that interweaves Mary Rogers’s story and Poe’s treatment of it with material on the rise of a modern police force in New York City and the power of the nineteenth-century tabloids. Rose’s book, which as the subtitle suggests, is a novelization of Poe’s attempt to turn the Mary Rogers story to his ownpurposes, is noteworthy for, among other things, a wonderful evocation of New York City in the mid-1800s and a compelling depiction of Poe in all his misery and glory.

Images courtesy of Zoo 22 and Ephemeral New York

Peggy Ehrhart is the author of the Maxx Maxwell mysteries, featuring blues-singer sleuth Elizabeth “Maxx” Maxwell. Visit Peggy on the web at www.PeggyEhrhart.com.

I have just taken down from my bookshelf Rick Geary’s beautifully-drawn and thoroughly engaging The Mystery of Mary Rogers; one of his Treasury of Victorian Murder series, published by NBM Comics Lit in 2001. It is now in my ‘to read’ pile.

There, that should send you off on the chase… It is worth the effort.

[b]Feu[/b]

Thanks, good post. I just picked up the Stashower book, looks fun.