A supervillain walks into a bar and orders a drink. When the bartender says to him, “We don’t serve your kind,” the villain and his brother are cornered by government agents, one dies, and the other is severely injured and placed in witness protection. Or something like that.

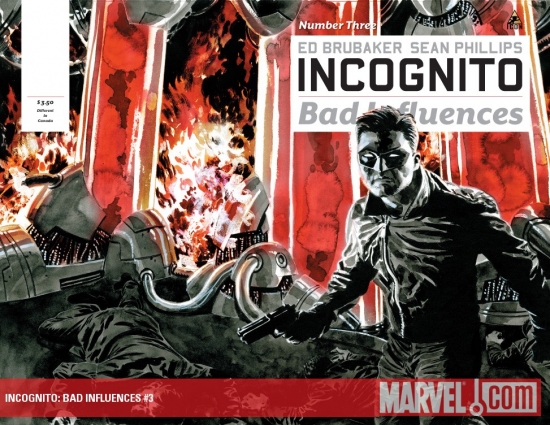

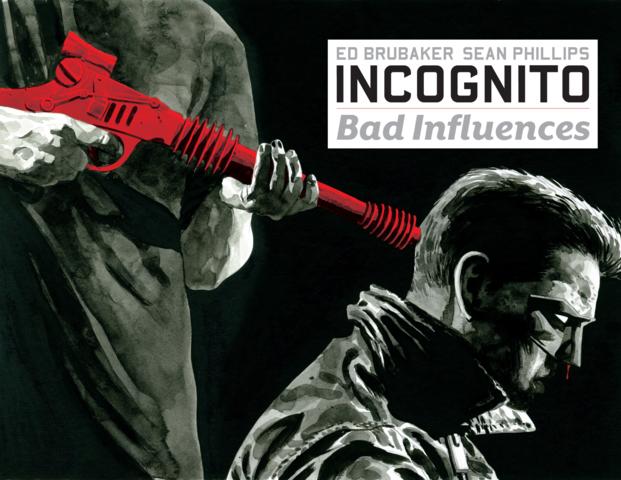

In Incognito, the brainchild of Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips, there is a group of supervillains and a group of government agents, military officials, and scientists trying to keep them contained. The good guys are an organization, not unlike the Men in Black, whose sole responsibility is to make sure the public never knows that there are super-powered felons causing all the havoc they see on their city streets. For example, if a bad guy who can, say, shoot fire from his mouth causes a rupture in the pipes in a downtown office building, the news reports would be of a freak tornado. Get the idea?

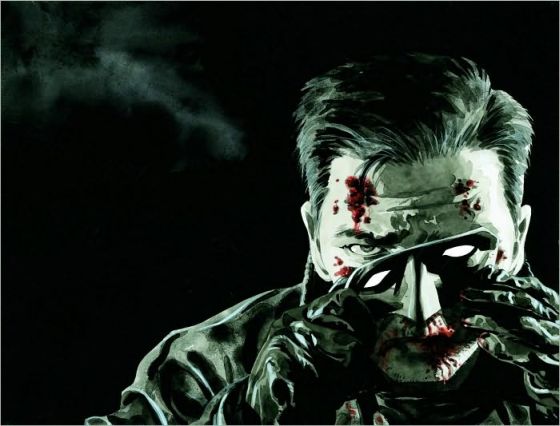

For all the antics of these meta-humans, Brubaker tries his best to create a normal world, as normal as the opening frames anyway. A guy in a domino mask thwarts an intended mugging and rape of a young woman. In these action scenes, artist Phillips introduces more realism into this fray than your typical Spider-man versus Doctor Octopus, sending blood spraying from broken mouths and leaving crimson splotches on brick walls. This isn’t your father’s superhero. And the soon-to-be named Zack Overkill isn’t your typical superhero.

In fact, he’s a supervillain. In the witness protection program. With quick flashbacks, we learn that Overkill—gotta love the meta-nature of that name, huh?—is a former supervillain who testified against his boss, the Black Death. Now, Overkill is a mindless office drone, bored out of his skull. That’s where the trouble starts.

Brubaker posits a few questions that are new to the comic world. One example: how do you stop a supervillain from doing all of his super bad stuff? As always, the government has a solution: drugs. The agency, SOS, gives Overkill a dose of something to limit his powers. What they don’t figure in is Overkill’s search for release from boredom through illegal street drugs. Since this is an amalgamation of crime comics and superhero comics, the illegal remedies counteract the legal ones, and we have ourselves a story. What started out as a straight-up, noir-ish, hard-boiled crime story morphs into something quite different as soon as Overkill rips the door off of a car. Oops. That goes double when, in a faraway laboratory, Overkill’s former compatriots detect his presence. The Black Death, a telepath being held in a maximum-security prison, sends out orders to eliminate Overkill.

Brubaker posits a few questions that are new to the comic world. One example: how do you stop a supervillain from doing all of his super bad stuff? As always, the government has a solution: drugs. The agency, SOS, gives Overkill a dose of something to limit his powers. What they don’t figure in is Overkill’s search for release from boredom through illegal street drugs. Since this is an amalgamation of crime comics and superhero comics, the illegal remedies counteract the legal ones, and we have ourselves a story. What started out as a straight-up, noir-ish, hard-boiled crime story morphs into something quite different as soon as Overkill rips the door off of a car. Oops. That goes double when, in a faraway laboratory, Overkill’s former compatriots detect his presence. The Black Death, a telepath being held in a maximum-security prison, sends out orders to eliminate Overkill.

While that is certainly one problem, it’s not his only problem. Were this a typical superhero story, you'd have the main characters robbing banks or causing all sorts of mayhem. Overkill, for some reason, seems to enjoy the being a hero. It's causing him to question his own existence, and whether or not a man born—or in Overkill’s case, created—with certain abilities and tendencies can change. That is if a man is born to be bad, can he become good?

While that is certainly one problem, it’s not his only problem. Were this a typical superhero story, you'd have the main characters robbing banks or causing all sorts of mayhem. Overkill, for some reason, seems to enjoy the being a hero. It's causing him to question his own existence, and whether or not a man born—or in Overkill’s case, created—with certain abilities and tendencies can change. That is if a man is born to be bad, can he become good?

We read comics and enjoy the movies made from them because we like clarity. Superman is Superman. The Kryptonian doesn’t alter his course. You know he isn’t going to just up and kill someone. You name your mainstream hero, and I’ll show you a good person at the core of their being. Even the grittier ones like Wolverine and The Punisher have, at their centers, virtuous goals, even if they go about them through violence and destruction.

The same is true in crime literature and movies. There’s a nice comfort in watching episodes of Dragnet or Perry Mason because, no matter how bad it gets for the hero, he will win. True, that got boring after a time, so more fallible characters appeared on the scene. I’m thinking of Mike Hammer, “Popeye” Doyle, or Jimmy McNulty here, to name just a few. You could even throw Jack Bauer in with these guys. Brubaker sets Incognito apart by focusing on the bad guy. Can a man so used to devastation and death stop himself? Can he pull his punches, so to speak? What kind of man decides that his core nature is wrong and changes?

It's a question Overkill wrestles with as he is blackmailed by his co-worker who has given him an ironclad alibi with Overkill’s probation officer. It’s also the same question he has to ask himself as he confronts his evil twin, or third, as it were. Hey, as real-world as the prose and art styling are, Brubaker and Phillips pull from the great pulp lineage and reveal Overkill is a laboratory experiment. The twin he knew about died years before. The twin (third) he didn’t know about is pure evil, killing and maiming just because. They fight and, well, remember what I said about Dragnet? Good guys win.

It's a question Overkill wrestles with as he is blackmailed by his co-worker who has given him an ironclad alibi with Overkill’s probation officer. It’s also the same question he has to ask himself as he confronts his evil twin, or third, as it were. Hey, as real-world as the prose and art styling are, Brubaker and Phillips pull from the great pulp lineage and reveal Overkill is a laboratory experiment. The twin he knew about died years before. The twin (third) he didn’t know about is pure evil, killing and maiming just because. They fight and, well, remember what I said about Dragnet? Good guys win.

There are echoes of Superman’s journey in the sub-text of this story. Overkill, when he was all bad, didn’t care about the people he hurt. His time with the good guys, the day-to-day life of an office, seeing and interacting with “normal” people, did something to him, I think. The battles between Superman and the other Kryptonians (yes, there are more than just one) boil down to one thing: Superman cares for the people of Earth because people on Earth raised him. While he is simultaneously Kal-El of Krypton and Clark Kent of Earth, the Kent side usually wins. Overkill changes after seeing life on the other side. By the end of the story, he still doesn’t know who he is, he just knows what he isn’t. At least that’s a start.

Crime Comics & Graphic Novels have their own feature area where you can read about how Darwyn Cooke's The Hunter shows Richard Stark's famous creation Parker as a tougher version of Don Draper.

Scott D. Parker is a professional writer who discusses books, music, and history on his own blog, and is a regular columnist for Do Some Damage.

INCOGNITO looks all kinds of good, Scott. Thanks for the review. I’m always looking for graphic novels/comics that turn the page.

As long as its not Superman. (Inside joke.)

David – This one surprised me. I don’t think Brubaker is capable of writing a bad story, but this one soared higher than I expected.

It’s also ironic to re-read this review that I wrote before my current interest in Superman.

How is this superhero comic in any way like pulp: “Brubaker and Phillips pull from the great pulp lineage”?? They are two different things. Superhero comics have their own great lineage, no reason to drag pulp into it.