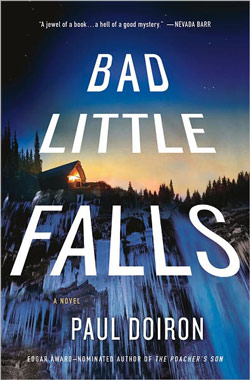

Maine game warden Mike Bowditch has been sent into exile, transferred by his superiors to a remote outpost on the Canadian border.

When a blizzard descends on the coast, Bowditch is called to the rustic cabin of a terrified couple. A raving and half-frozen man has appeared at their door, claiming his friend is lost in the storm. But what starts as a rescue mission in the wilderness soon becomes a baffling murder investigation. The dead man is a notorious drug dealer, and state police detectives suspect it was his own friend who killed him. Bowditch isn’t so sure, but his vow not to interfere in the case is tested when he finds himself powerfully attracted to a beautiful woman with a dark past and a troubled young son. The boy seems to know something about what really happened in the blizzard, but he is keeping his secrets locked in a cryptic notebook, and Mike fears for the safety of the strange child. Meanwhile, an anonymous tormentor has decided to make the new warden’s life a living hell. Alone and outgunned, Bowditch turns for assistance to his old friend, the legendary bush pilot Charley Stevens. But in this snowbound landscape—where smugglers wage blood feuds by night—help seems very far away indeed. If Bowditch is going to catch a killer, he must survive on his own wits and discover strength he never knew he possessed.

Chapter 1

The last time I saw Lucas Sewall, he left a school notebook under the passenger seat of my truck.

It was a curious document. The boy had drawn disturbing images on the covers—pictures of vampire women and giant owls with bloodstained beaks. The inside pages were crammed with his indecipherable handwriting, words so small you needed a magnifying glass to read them. There were maps labeled with cryptic directions to “lightning trees” and “old Injun caves” and hieroglyphs that might have been messages in secret code or just meaningless scribbles. With a compulsive liar like Lucas, you never knew whether you were dealing with fact or fiction.

The dated diary entries were especially hard to unravel. Between his other weird jottings, the kid had seemingly kept a careful record of the tragic events in Township Nineteen, as if he had anticipated that his eyewitness account might one day prove useful in a court of law. But who knows what was going on in that oversize head of his? In my short acquaintance with him, I learned Lucas Sewall was a deeply damaged child who believed in manipulating adults, settling scores, and tying up loose ends. Sometimes I wondered whether he didn’t see the notebook as his last will and testament, with me in the role of executor.

The first entry was dated three nights before the fatal snowstorm:

February 12

Randle came around last night drunker than usual and made us leave the house again so he could get at his stash of drugs without us knowing where he’d hid them.

Ma didn’t want to let him in, but Randle had the Glock he bought off that Mexican in Milbridge and said he’d use it this time if we didn’t wait outside in the dooryard while he got his pills and powder.

We had trouble bringing Aunt Tammi down the ramp on account of her wheelchair not having good grippy-ness on the ice and snow.

Ma said we should at least wait inside the car, where we could run the blower, only she’d forgotten the keys on the kitchen table. That just made her more pissed off than she already was.

We could’ve waited in Randle’s car except that Uncle Prester was passed out in the shotgun seat and he smelt like he’d puked himself, which wouldn’t be the first time.

Randle was inside the house a long time, making shadows behind the curtains. When he came out, Ma said they were broken up forever and she didn’t like him hiding his drugs in her house for the cops to find.

That got Randle all exercised. He said if she ever ratted on him, she’d be sorry, and he said that went double for the Boy Genius.

Randle didn’t figure that I’d already found his stupid drugs stuffed behind the insulation in the sewing room . . . easiest place in the world to find, on account of the pink dust all over the floor.

He didn’t know what I did to the pills, neither . . . and wasn’t he in for a wicked surprise when someone swallowed one of them Oxycottons?

I would pay GOOD money to see Randle get his ass kicked.

As it happened, Lucas didn’t have long to wait.

Two days later, his mother’s ex-boyfriend was dead and his uncle Prester lay in a hospital bed with blackened claws where his fingers and toes had once been.

Chapter 2

The zebra had frozen to death beneath a pine tree.

The animal lay on its side in a snowbank with its striped legs rigidly extended and its lips pulled back from its yellow teeth in a horsey grimace, as if, in its final moments on earth, it had grasped the punch line of some cosmic joke.

The owner of the game ranch had called the local veterinarian in a last-ditch effort to resuscitate the hypothermic zebra, and Doc Larrabee had brought me along because he needed a witness to back up this crazy story down at the Crawford Lake Club. It didn’t matter that I was the new game warden in District 58 and a flatlander to boot.

Doc knelt in the snow beside the equine. He had removed his buckskin mitten and was rubbing his palm across the dead animal’s thinly haired haunches. The frost melted beneath the warmth of his hand.

“You understand that a zebra is a creature of sub-Saharan Africa?” he asked Joe Brogan.

“Yeah,” the ranch owner said sourly. “It is well adapted to life on the equatorial savanna—as opposed to the boreal forest of Maine, I mean.”

“I understand that!”

Brogan wore a beaver hat that might once have been fashionable on the streets of Saint Petersburg. His face was also furry. A single brown eyebrow extended across the bridge of his nose, and a luxuriant beard grew thickly down his throat before disappearing, like a shy animal, inside the collar of his wool shirt.

A small crowd of men had met us outside the gate of the Call of the Wild Guide Service and Game Ranch. They were big bearded men wearing camouflage parkas, synthetic snowmobile pants, and heavy pack boots. Now I could see their bulky silhouettes lurking in the shadows of the pines and smell their cigarettes drifting on the crisp February air. The ill will carrying downwind in my direction was as pungent as tobacco smoke.

The guides at Call of the Wild did some conventional outfitting in the fat spruce land outside the ranch’s barbed wire—leading hunters in pursuit of deer, bear, coyote, and moose—but Brogan had built his business on a practice that animal rights activists termed “canned hunting.” He owned miles of fenced timber, which he had stocked with the oddest menagerie of animals imaginable. The sign outside his gate advertised the services offered: RUSSIAN BOAR, BUFFALO HUNTS, RED STAG, ELK HUNTS, and FALLOW DEER HUNTS.

The zebra hadn’t survived long enough to make it onto the sign.

At Call of the Wild, hunters paid thousands of dollars to sit on thermal fanny warmers in protected tree stands and take potshots at exotic creatures. According to a strange loophole in Maine law, what happened on game ranches was generally not the concern of the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, for which I worked; rather, it was under the jurisdiction of the Department of Agriculture. The state basically viewed these places as farms and the foreign animals as livestock. In my mind, the entire setup was a disgrace and an embarrassment to sportsmen.

The Warden Service had just transferred me from midcoast Maine to the unpeopled hinterlands of Washington County. I’d gotten into some administrative trouble down south the previous spring and summer—not the first time for such things, and unlikely to be the last. My commanding officer never came right out and said I was being exiled to Siberia, but when you are reassigned to the easternmost county in the United States—a place known for its epidemic drug abuse, multigenerational unemployment, and long tradition of violent poaching—it’s pretty clear your career isn’t on the rise.

While Doc Larrabee examined the carcass, I documented the travesty with my Nikon.

“What are you taking pictures for?” Brogan asked.

“Souvenirs,” I said.

Brogan and I had already locked antlers a week earlier. I’d issued a criminal summons to one of his coyote-hunting guides, a meathead named Billy Cronk, when one of his clients discharged a firearm within a hundred yards of a residence on posted property. Given the unemployment rate in these parts, losing your commercial guiding license was a pretty big deal. On the other hand, Cronk’s customer could’ve killed the old woman who lived in that house, and in my book, that was an even bigger deal.

I glanced around at the cigarette-lit faces. “Where’s Billy tonight?”

Brogan spat a brown stream of tobacco juice at my feet. “None of your fucking business.”

My former supervisor had given me some advice before I was transferred to the boondocks. “Play it tough,” Sgt. Kathy Frost had said. “When you’re assigned to a new district, you need to come on strong, or people will think you’re a pussy. Especially way Down East, where they eat wardens for breakfast.”

Everywhere I’d gone for the past three weeks, people treated me like a leper.

Doc Larrabee was one of the lonely exceptions. Maybe he felt sorry for me, or maybe, as a recent widower living alone in an isolated farm house, he thought that hanging around with the hated new game warden would be the cure for midwinter boredom.

“Well, obviously the animal has expired,” said Doc.

“Obviously,” said Brogan.

“I would attribute the official cause of death to freezing its ass off.”

Larrabee was a slope-shouldered man in his early sixties. He wore round eyeglasses, which were constantly fogging over, requiring him to wipe away the moisture with a handkerchief. For reasons I couldn’t fathom, he wore an Amish-style beard: a fringe of hair along the jawbone, with no mustache to match. He was dressed in green coveralls and tall rubber boots fit for wading through all kinds of manure. His work as a large-animal veterinarian kept him busy in the outdoors—delivering breached foals and tending to sick cows—and he had the healthy glow of a person who breathes a lot of fresh air. On the drive over, he’d told me he was working on a book of his misadventures titled All Creatures Sick and Smelly.

“So that’s it, then?” the ranch owner said.

“Unless you have a musk ox or a greater kudu you’d like me to examine.”

Brogan moved the wad of tobacco in his mouth from one cheek to the other. “You’re one hell of a comedian, Doc.”

The veterinarian rose, stiff-kneed, to his feet. “I’m going to have to report this incident to the Animal Welfare Department, Joe,” he said, no longer grinning.

Brogan narrowed his eyes beneath his hairy brow. “What for?”

“Aggravated cruelty to animals is a Class C crime,” I said.

“I didn’t know it was going to freeze to death.”

“It’s a zebra, Brogan,” I said.

“We’ve got all kinds of animals here—African ones, too,” he said. “They all handle the cold fine.”

“Brogan,” I said. “It’s a zebra.”

“The guy who sold it to me said it was hardy. He misrepresented the animal. He’s the one you should be harassing.”

“I’m sure the district attorney will agree,” I said.

“Fuck you and your attitude,” Brogan said.

I heard murmuring and snow crunching in the shadows around me. My right hand drifted toward the grip of my holstered .357 SIG SAUER.

Two years earlier, when I’d been a rookie fresh from the Maine Criminal Justice Academy and full of self-righteousness, I would have welcomed a confrontation with this jerkwad. But I had made strides in managing my anger, and besides, there was no urgency here: The zebra was dead. I would hand over my notes and photos to the Animal Welfare Department, and that would be the end of my involvement in Brogan’s bad business.

Doc glanced at me and gestured in the direction of the gate, hundreds of yards away through thick snow and dense pines. “I’d say it’s time for us to go, Warden.”

“Gladly.”

Brogan, of course, had to have the last word.

“Hey, Bowditch,” he said. “You’re not going to last long around here if you don’t cut people some slack.”

“I’ll take it under advisement,” I said.

When we got back to the road, I half expected to find my tires slashed, but no one had molested the vehicle in our absence. My “new” truck, a standard-issue green GMC Sierra, was actually older than the pickup I’d been assigned in Sennebec. It seemed like all of my equipment here was shabbier than what I’d been issued before. Maybe being given obsolescent gear was part of my punishment.

Doc Larrabee drew his shoulder belt tight across his chest. When he exhaled, I caught the sweet smell of bourbon on his breath. “Well, that episode was definitely one for my book,” he said.

I started the engine and turned the wheel east, in the direction of Calais—pronounced Callus in this part of the world—on the Canadian border. “I can’t believe that idiot brought a zebra to Maine.”

The veterinarian rubbed his mittens together. “Joe’s not as dumb as he looks. He’s smart about looking after his own interests. And like most bullies, he has an eye for a person’s weak spot. Those men who work for him are all terrified of pissing him off.”

Doc’s description of Brogan reminded me a lot of my own father. Jack Bowditch had always been the scariest guy in whatever town he’d happened to be living. Out in the sticks, where people live far from their neighbors and are leery of reporting misdeeds to the authorities out of fear of violent retribution, a reputation for ruthlessness can get a man most anything he wants.

“My new supervisor warned me about Brogan,” I said.

“How is Sergeant Rivard?”

As big a prick as ever, I wanted to say.

Like me, Marc Rivard had been transferred from the affluent south to dirt-poor Washington County some time back, and he was still bitter about his circumstances. Unlike me, he had subsequently earned a promotion and was now in the position of off-loading his frustrations on the nine district wardens under his supervision.

“Sergeant Rivard has a unique approach to his job,” I said.

Doc removed his glasses and wiped them with a snotty-looking handkerchief. “Do you mind if I ask you a personal question? Did you impregnate the commissioner’s daughter or something? You must have pissed off some eminence down in Augusta to get stationed out here in the williwags.”

I found it hard to believe Doc was truly ignorant of my notorious history. If he read the newspapers at all, he must have known about the manhunt for my father two years ago and he would have heard that I’d shot a murderer in self-defense back in Sennebec last March. Maybe he didn’t realize how deeply I’d embarrassed the attorney general’s office in the process. In the opinion of the new administration in Augusta, I had become a public-relations nightmare. And if Colonel Harkavy couldn’t force me to resign, he could at least sweep me under the rug.

“It’s a long story,” I said.

“I’d enjoy hearing it sometime,” Doc said. “I might be misreading your social calendar, but I’m guessing you don’t get many dinner invitations. Why don’t you come over tomorrow night and I’ll cook you my widely praised coq au vin. After Helen died, I had to learn how to feed myself, and thanks to Julia Child, I became quite the French chef.”

I didn’t much feel like socializing these days, and the idea of eating dinner alone at this old man’s house made me squirmy, I’m not ashamed to admit.

The veterinarian must have sensed my discomfort. “Maybe I’ll invite Kendrick over, too,” he said. “He’s a professor down to the University of Maine at Machias and runs the Primitive Ways survival camp. Kevin’s a musher, a dogsled racer. He and his malamutes have raced in the Iditarod up in Alaska a couple of times and finished in the money. He’s had a pretty unusual life and is something of a living legend around here. He knows these woods better than the local squirrels.”

Kendrick’s name was familiar to me. My friend, the retired chief warden pilot, Charley Stevens, had mentioned the professor as someone worth getting to know in my new district. My one consolation in being transferred Down East was that it moved me closer to Charley and his wife, Ora, who had recently purchased a house near Grand Lake Stream, an hour’s drive north of my new base in Whitney.

I tried to put Doc off, but he was persistent.

By the time I dropped the veterinarian at his doorstep, we had agreed that I would join him for dinner the following evening.

I took my time driving home. It wasn’t like I had anyone waiting for me in bed.

The moon was nearly full, so I paused for a while atop Breakneck Hill and gazed out across the snowy barrens, which extended as far as the eye could see. Washington County is the wild-blueberry capital of the world. During the never-ending winter, the rolling hills become covered with deep drifts of snow. In places, boulders jut up through the crust. At night, the slopes look almost like a lunar landscape, if you can imagine twisted pines on the moon and a looming cell tower blinking red above the Sea of Tranquility.

I switched on the dome light and reached for the birthday card I’d tucked between the front seats. It had arrived in my mail that morning, just a week late. The picture showed a cartoon cat hugging a cartoon dog.

To a purrfect friend, it read.

Sarah had always given me ironic cards—the sappier the better—so why should it be any different now that our relationship was over? She’d handwritten a note in purple ink inside:

Dear Mike,

I hope things are well and that you’re enjoying the winter Down East. Do you have any time to ski or ice fish?

How are Charley and Ora doing? I know it’s not your way to do something special for yourself, but it would make me happy to think of you having some fun with friends today.

Life is busy here in D.C., but it’s stimulating work and I’m meeting lots of fascinating people. One of these days we should catch up—it’s been so long since we talked.

xoxo

S.

I didn’t really want to speak with my ex-girlfriend. Sarah and I were finished forever as a couple, and probably finished as friends, no matter what her birthday card said. A year earlier, she had become pregnant with my child, a condition she had hidden from me until she miscarried. The fact that she had concealed her pregnancy proved that she would never overcome her doubts about my fitness to be a husband and father. We had broken up by mutual agreement over the summer, before I’d received my transfer to the North Pole. She was now living in Washington, D.C., working for the national office of the Head Start program. Sometimes I pictured her going out for drinks with people our own age—with men our own age—while I was stuck in the wilds of eastern Maine, fielding dinner invitations from elderly veterinarians.

I’d been struggling to find meaning in the sequence of events that had led me to this wasteland, but my prayers always seemed to disappear into the black void that stretched from horizon to horizon, and I never got any answers. All that was left to me was to accept my fate and do my job with as much dignity as I could muster.

Tonight, however, I found myself yearning to hear Sarah’s voice, even though I knew that speaking with her would make me feel more lonely and not less. Two years earlier, when we were weathering a rough patch, I had convinced myself that I was a lone wolf by nature.

It was the reason why I had chosen the profession of game warden—because I secretly wanted a solitary life.

Now I knew better.

The moon was high and bright overhead when I arrived at my trailer on the outskirts of Whitney. I’d lived in my share of mobile homes as a child, and this one was better than most. The roof barely leaked, all but two of the electrical sockets worked, and a rolled towel pressed against the base of the door was enough to stop the snow from blowing in through the crack. My rented trailer was located down a dead-end road, far enough from the main drag that I could park my patrol truck out of sight—although every poacher, pill addict, and petty criminal within a hundred miles knew where I lived.

As I turned the truck into the plowed drive, the bright halogen bulbs swept across the front of the building. Something long and dark seemed to be affixed to the door. I couldn’t tell for sure what the black thing was until I climbed the steps with my flashlight in hand.

The object was a coyote pelt. Whoever had killed the animal had done a poor job of skinning it, because the fur stank to the heavens. A tenpenny nail had been driven through the head into the hollow metal door.

There was a note written in block letters, large enough for me to read in the moonlight: “WELCOME TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD.” It was signed, “GEORGE MAGOON.”

Copyright © 2012 by Paul Doiron

Bestselling author Paul Doiron is the editor-in-chief of Down East: The Magazine of Maine. A native of Maine, he attended Yale University and holds an MFA from Emerson College. His first book, The Poacher’s Son, is the winner of the Barry award, the Strand award for best first novel, and a finalist for the Edgar and Anthony awards. Paul is a Registered Maine Guide and lives on a trout stream in coastal Maine with his wife, Kristen Lindquist.