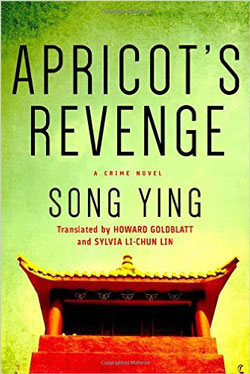

Apricot's Revenge by Song Ying is a thought provoking detective novel about a high-profile murder that explores social issues in modern day China (Available February 16, 2016).

Apricot's Revenge by Song Ying is a thought provoking detective novel about a high-profile murder that explores social issues in modern day China (Available February 16, 2016).

A business tycoon in China is found dead; he apparently suffered a heart attack while swimming. His body is washed onto a beach in a popular resort known as the Hawaii of the East. But soon it becomes clear that he was murdered. Three immediate beneficiaries of his death become the suspects: the vice president of the company, Zhou, who is in line to take over his position; his young widow, Zhu, who stands to inherit a huge amount of wealth; and his arch business rival, Hong, who is competing in a bid over a piece of hot property.

Nie Feng, a young investigative reporter for a magazine, interviewed the victim just a few days before he died. Through his own research, Nie Feng discovers a new suspect who is not on the police’s radar.

ONE

Fog Over Lesser Meisha

— 1 —

Lesser Meisha, an enchanting beach.

A famed seaside resort in Shenzhen, it was known as the “Hawai’i of the East.” Swarms of vacationing tourists came every weekend to relax on the sand, ride the waves, or just play in the water.

A line of beach tents along the water’s edge created a unique scene as night fell. Shaped like yurts or pyramids, they came in a variety of colors—reds and blues and yellows—and from a distance looked like flowers blooming in the setting sun. At eighty yuan a night, they were the favorite lodging choice for young tourists and lovers on vacation, both because they were so much cheaper than the five-hundred-a-night Seaview Hotel and because they were much more romantic. The tents were thrown up as dusk descended, when a pleasant breeze blew in from the sea. Young vacationers began to sing and dance, while others slept to the relaxing accompaniment of ocean waves. Was there anything better than that?

Six o’clock, or thereabouts, on the morning of June twenty-fifth. Dawn had barely broken when a couple emerged from one of the tents. Lovers, apparently. He was wearing glasses and was dressed in jeans that failed to hide his beer belly. The woman, in a yellow T-shirt over a short white skirt, was not pretty, but her youth made up for that. He had his arm around her waist, contentment from a night of pleasure written all over his face. She smiled shyly and playfully pushed him away. They had arrived the previous afternoon. Beer Belly managed a computer company; she worked as his secretary or, to use the popular term, his Secret Sweetheart.

Obviously still savoring their night together, they looped their arms around each other and strolled along the misty early-morning beach, padding pleasurably across the spongy sand in bare feet. Gentle waves left rings of white foam on the sandy shore.

The jutting rocks of Chao Kok were visible through the thin layer of fog that lay over the ocean.

“Dapeng Bay is such a beautiful spot,” the woman said.

“‘All my best to you, O eternal ocean! The sound of your waves reminds me of my hometown.…’” Beer Belly spread his arms melodramatically as he declaimed lines of poetry.

“What’s with you this morning?” She mocked him with a smile.

“That’s a poem by Heine.”

“Who’s Heine?”

Beer Belly smirked. “You don’t know Heine, the famous German poet? Then you probably haven’t read his ‘Ode to the Sea.’”

“No.”

“I’ll show it to you next time.”

“I won’t read it.”

“I should think you’d be bored with Murakami by now.”

“I like him. Especially Dance Dance Dance. It’s beautiful.”

“Right, that Sheep Man again. He’s weird.”

“I don’t care. I like him.”

“Hey, look up there.” Beer Belly pointed into the sky.

She looked up in time to see white birds passing silently overhead.

“Seagulls. They’re so pretty,” she said with a squint.

“Wrong again. Look carefully, they’re egrets.”

The birds were a picture of grace and ease, long legs stretched out behind them.

“Why are there egrets at the beach?”

“Because they want to dance dance dance,” Beer Belly teased.

“Stop that!”

“See those nests in the trees?” He pointed to a spot at the far end of the beach, where Qitou Ridge rose a hundred meters into the sky and cast a verdant shadow.

With a cry, the egrets flew off toward the ridge.

At the base of Qitou Ridge was another of Lesser Meisha’s selling points—Lovers’ Lane. Sandwiched between the hill and the beach, it meandered around a towering banyan tree and led to Guanyin Cliff at the top of the hill, where, after continuing down a dozen paces or so, it crossed a small wooden bridge that led to Chao Kok, the area’s best spot for ocean viewing.

Following the direction of the flying egrets, they headed west, leaving fresh footprints in the sand.

The crags of Chao Kok, which extended into Dapeng Bay, slowly emerged from the morning fog.

They stopped just before they reached the pier at the far end of the beach, having spotted what looked like a naked man lying in the sand near the stone jetty. Not far from where he lay, craggy rocks nestled up against a breakwater that rose to about the height of an average adult. Above it was Lovers’ Lane.

Curious, Beer Belly and his lover walked up to the stone jetty, suddenly sensing that something was wrong with the man.

Barefoot and wearing only a red bathing suit, he lay facedown, his legs spread out away from the water; apparently, he had washed up on the morning tide. His head was resting on his right arm, facing away from them.

Beer Belly squatted down and placed his finger under the man’s nose. Nothing.

He touched the man’s bare arm; it was cold.

“He … he’s dead!” Beer Belly said in a shaky voice.

The woman’s face paled; she couldn’t speak.

The man looked around, no one else was in sight.

“Should we call the police?” he asked.

“What do you think?”

Their secret tryst would be exposed if they became police witnesses.

“I guess we should,” Beer Belly concluded.

She nodded, reluctantly.

They rushed back, found the white cabin with a LESSER MEISHA TOURIST OFFICE plaque on the door, and woke up the night clerk.

“A drowned man washed up on the beach last night,” Beer Belly said—shouted, actually.

“What did you say? Someone drowned?” The stunned clerk rubbed his sleepy eyes.

To ensure swimmers’ safety, watchtowers staffed with lifeguards had been installed all up and down Lesser Meisha Beach. That, of course, was no guarantee of safety, and accidents did occur from time to time, especially when all the bathers looked like dumplings bobbing up and down in a pot. The lifeguards could not see everything, and were only on duty during the day, anyway, so people who enjoyed an evening dip took their chances. No one but an experienced swimmer or a die-hard skinny-dipper would risk going into the water alone at night.

The clerk called the local police station.

Fifteen minutes later, two uniformed cops arrived.

Since the body had been discovered near the pier, beyond the designated swimming area, the policemen reported the situation to the Public Security Bureau. Half an hour later, Cui Dajun, head of the Y District Criminal Division, drove up with a team of officers and technicians. They parked their blue-and-white Jetta police cars behind the Lovers’ Lane railing above the scene and cordoned off the area with yellow tape.

By that time the sun was out, but the fog lingered.

A gentle morning light bathed the distant tents. The beach was deserted except for a few early risers down at the far end gathering seashells.

Cui Dajun, a man in his midthirties, wore his jacket unbuttoned, exposing a white-striped T-shirt. Though he was short—under five feet seven—he had eyes that could bore right through a person. He asked Beer Belly and his lover to describe how they’d discovered the body, while his young assistant, Officer Wang Xiaochuan, took their statement. Another officer, a woman by the name of Yao Li, stood next to Cui and watched intently as the eyewitnesses told their story.

The two local cops were posted at the restricted area marked by the yellow tape.

After the questioning, Wang had Beer Belly and his lover sign their statement.

“We’ll contact you if we need more information.”

They nodded, and Cui told them they could leave.

Meanwhile, the investigation was under way: a tall man in a vest stenciled with the word POLICE took a camera from his black case and began taking pictures from all angles.

The dead man, in his mid to late fifties and wearing only a red Lacoste bathing suit, had a medium build, though he was slightly overweight. The body lay on a smooth stretch of beach near the craggy rocks, not far from the roadbed beneath Lovers’ Lane. Traces of white foam from the rising tide were visible four or five meters from his feet.

There were no footprints on the beach except for those left by the eyewitnesses, but even if there had been before that, they’d have been washed away by the incoming tide. No personal effects or clothing in the vicinity. Not far from the body, a stone jetty stretched from the pier into the water. At high tide, waves crashed against the jetty, producing a rhythmic roar from crevices among the rocks.

Tian Qing, the bespectacled medical examiner, squatted down to examine the man’s back and the back of his head, gently pressing with his fingers here and there. When he turned the body over, someone remarked that the dead man’s face looked familiar. Grains of sand were stuck to his broad forehead and the tip of his nose. The face was a purplish gray; so were his lips.

“He looks a little like the CEO of Landmark Properties, Hu Guohao,” the chunky young officer, Wang Xiaochuan, muttered.

“You know this man?” Cui gave him a questioning look.

“I think I saw him on TV a few nights ago, on the show Celebrity Realtors. There was a close-up of him,” Wang said.

The tall officer with the camera came to take pictures of the dead man’s face.

“I think I’ve seen his picture, too,” Yao Li, the other officer, commented.

“I guess it does look like him,” Cui said after studying the man’s face carefully. He continued with a surprised voice, “but how can that be?”

— 2 —

Hu Guohao was a prominent Shenzhen realty tycoon, the helmsman of Landmark Properties, South China’s realty flagship. As a wealthy and influential businessman in Southern Guangdong, he was always in the limelight, was a member of the Shenzhen Political Consultative Conference, had been selected as one of the outstanding entrepreneurs of Guangdong Province, and was on the top ten list of Southern China’s realty celebrities.

If it was indeed Hu Guohao, the news would rock the city.

Cui took out his cell phone and dialed 114 for information.

“I need the switchboard number for Landmark Properties … Got it, thanks.”

He tried the number, but no one answered.

He called again, still no answer.

Someone finally picked up on the third try.

“Hello?” The operator sounded as if she had just gotten up.

“Is this Landmark Properties? I’d like to speak with your CEO.”

“I’m sorry, but everyone’s off today,” the operator said lazily. “There’s no one in the office.”

Cui’s face hardened as he shouted into his phone: “Are you telling me that in a big company like yours no one works on Sunday?”

“Er, hold a moment.”

The call was transferred to a duty office, where a man with a deep baritone voice answered.

“May I ask what this is about?”

“I’m with the Public Security Bureau, Y District,” Cui said. “I need to speak to your CEO. It’s urgent.”

“Oh, he’s not in on Sundays.”

“How can I reach him?”

“Well,” the man paused. “I can give you his driver’s cell number.”

Two minutes later, Cui had Hu’s driver, a fellow named Liu, on the phone.

“Is this Mr. Liu? Where are you at the moment?”

“Who’s this? I’m home, in Beilingju.”

“This is Cui Dajun, head of the criminal division of the Y District branch of Public Security. I have an urgent matter to discuss with your CEO, Mr. Hu Guohao.”

“Oh, Mr. Hu went to Greater Meisha yesterday.”

“Greater Meisha? What time was that?”

Cui signaled Xiaochuan with his eyes that it must be Hu Guohao; they both tensed.

“Yesterday afternoon. I drove him there.”

Greater Meisha, another beach resort on Dapeng Bay, abutted Lesser Meisha. According to Liu, Hu Guohao had gone there to swim the previous day, something he did on most Saturdays, sometimes with clients, other times alone. He’d spend the night at the Seaview Hotel and return home Sunday afternoons. Liu had driven him to the beach in his black Mercedes the day before, Saturday, arriving at three fifteen. A room had been reserved under his name. Liu returned to Shenzhen after Hu told him to pick him up Sunday at four.

“Something may have happened to your boss. Come to Lesser Meisha right away.”

“Did you say Lesser Meisha?” the driver asked.

“Yes. Lesser Meisha.”

Cui closed his cell and told Xiaochuan and Yao Li, “Go check out the Seaview Hotel at Greater Meisha.”

“We’re on it.” They left, following the shoreline.

The sun was up and shining brightly by then, and people were beginning to appear on the beach. Curious tourists wanting to get a closer look were stopped by the two local cops, who kept them beyond the yellow tape.

Cui looked at his watch, telling himself that news of a dead body on Lesser Meisha would soon be all over Dapeng city.

About a half hour later, Hu’s driver drove up to the Seaview Hotel in the Mercedes. He seemed pale and anxious, and his red polo shirt seemed out of place at the scene.

He identified the body—as expected, it was Hu Guohao. “Mr. Hu liked to swim at night,” he stammered, looking quite distressed. “He said the water was cooler.”

“Was he a good swimmer?” Cui asked.

“Yes. He could swim five or six kilometers with no problem.”

“So that means he could swim all the way from Greater Meisha over here to Lesser Meisha?”

“I’m pretty sure he could.”

“But why did he drown?” Medical Examiner Tian asked.

“That’s a good question.” Liu was still in shock. He hesitated. “But Mr. Hu did have a history of heart problems.”

“Heart problems?” Cui mulled that over.

Xiaochuan drove up with Yao Li from Greater Meisha in one of the Jettas. He’d barely parked the car before jumping over the railing with his report.

“We found Hu’s hotel registration and some other important information at the Seaview Hotel.”

“All right, tell me what you’ve learned.” Cui led them away from the crime scene.

Xiaochuan told Cui that, according to the hotel staff, room 204 had been reserved under Hu’s name on Friday and that he’d checked in Saturday afternoon at three twenty. The hotel was a stone’s throw from the beach, an ideal spot to enjoy an ocean view and convenient for swimmers. The room rates were high, but Hu was a frequent guest. Xiaochuan was told that Hu was relatively free with his money and enjoyed flirting with the female staff. He was well known there. Someone had seen him enter the hotel and take the spiral staircase to the second floor the day before. Ah-yu, a waitress in the Seaview Restaurant, told them that Hu had had dinner with a tall man the night before. They’d talked for a while before Hu left alone. The tall man had sat for another ten minutes before getting up to leave.

“Did you get a name?” Cui asked.

“Yes, we did,” Xiaochuan said, looking pleased with himself. “Hong Yiming, General Manager of Big East Realty.”

“You’re sure?” Cui persisted.

“Yes.” Yao Li added, “The hostess at the restaurant, a Miss Bai, knew Hong by sight. Both men were frequent guests at the hotel.”

“Very good.” Cui was pleased with the report. “Did anyone see Hu go out for a swim after seven o’clock?”

“There were too many swimmers at Greater Meisha last night, and no one noticed a thing. We even went to the locker room, but didn’t find Hu’s clothes or anything left behind by other swimmers.”

Cui liked the way things were moving.

“Hong Yiming might have been the last person to see Hu Guohao alive. Find him as soon as possible and see what he knows.”

“Yes, Chief.”

“I hope this is a simple drowning case,” Cui said wistfully, before they gathered up their gear to head back.

If only he could convince himself of that. Greater Meisha was four or five kilometers from the tourist center of Lesser Meisha, and he was puzzled why Hu’s body would wash up so far from where he’d started. Besides, they hadn’t found his clothes or any personal effects either on the beach or in the locker room.

The only possible explanation was that he’d swum from Greater Meisha across the shark barrier, had suffered a heart attack and drowned. The tide had then carried his body up to the beach.

As Cui was turning to leave, his gaze fell on the stone jetty that jutted out into the bay. But why had the body washed up so close to the pier?

— 3 —

Room 707 at the White Cloud Hotel in Guangzhou.

Eight a.m., Monday morning. Nie Feng woke up to the sound of a ringing telephone.

“This is your wake-up call, sir.”

“Oh, thanks.” Nie yawned and leaped out of bed.

A journalist and special-feature writer for Western Sunshine magazine, Nie Feng was a swarthy, athletic-looking man in his early forties. Sporting a crew cut, he had a likable, smiling face. As a top student in Sichuan’s C University School of Journalism, with a double major in psychology, he was highly valued by his editor-in-chief.

He’d worked until three that morning to finish a special feature for Western Sunshine, accomplishing the task that editor-in-chief Wu had been pushing him to wrap up. Now he could finally relax. A business trip to the Pearl River Delta area was a rare treat, so he’d made prior arrangements to visit a publisher friend in Zhuhai and see how well the magazine was doing in the south. Western Sunshine, a newcomer from the southwest, was a broad-ranging, full-color magazine with a cultural focus, and an influential publication with both domestic and foreign circulation. Wu was a seasoned pro who placed stringent demands on his contributors; it was he who’d come up with the Western Sunshine mission statement: Unique viewpoint—New ideas—A Showcase for the cultural tastes of China’s West.

Nie quickly washed up and went downstairs to the White Cloud Terrace for morning tea.

The Cantonese love their morning tea; diners can choose from an array of dim sum in steamers on small carts pushed around by smiling waitresses. A dazzling display of steaming, bite-sized items appears when the bamboo covers are removed: green-crystal buns, shrimp dumplings, golden chestnut cakes, mara layer cakes, and so on. Naturally, each meal translates into a hefty charge. Back in Chengdu, two meaty buns, a bowl of congee, and a plate of pickled cabbage cost no more than one and a half yuan, while in Guangdong, a bowl of congee, two steamed vegetables, and a dessert easily cost thirty or forty yuan. Since breakfast was not included in the room charge, Nie rarely splurged for morning tea when he checked into a hotel to write one of his feature articles.

He walked into the crowded restaurant, where natty businessmen in groups of four or five or as few as two were smoking and talking on their cell phones or with one another. There was also a family that spanned several generations, out for morning tea and happily sending snippets of melodious but incomprehensible Cantonese his way.

Nie took a seat in a red cloth chair in a side room; a waitress in a checkered blouse came over with a tea menu.

“What kind of tea would you like, sir?”

Opening the menu, he was shocked by the prices.

Gold Brand Iron Buddha, 138 yuan per person.

Ginseng Iron Buddha, 60 yuan per person.

Royal Century, 38 yuan per person.

The list went on.

He quietly turned to the second page, where he found and ordered the common High Mountain Iron Buddha, at ten yuan a pop. Later he learned that ordering tea was not required.

After the tea arrived, the waitress placed a yellow order form on the table, with the detailed prices for dim sum. He checked off several breakfast items: congee with lean pork and a thousand-year egg, steamed chicken feet with shredded peppers, spareribs steamed in preserved soy sauce, and a steamer of tiny meat buns.

It took hardly any time for the food to arrive, and Nie set to work. The chicken feet had a strong flavor and were quite tasty.

A newspaper rack displaying local as well as Hong Kong and Guangdong newspapers stood against the wall by the next table.

As he ate his congee, he reached out for a Guangdong morning paper.

South China newspapers are known for their more elevated approach to journalism, with serious cultural content and economic sophistication; they rarely rely on gossip and exotica to attract readers. They were Nie’s favorites.

The major front-page news of the day:

CHINA “JOINING THE WORLD” ENTERS THE SUBSTANTIVE PHASE OF MULTILATERAL TALKS

“WIND AND CLOUD” SATELLITE IS SUCCESSFULLY LAUNCHED

There was also an item about the human genome map. According to the Associated Press, two American research groups would make a joint announcement that the map was essentially completed. Experts described the research as biology’s equivalent of the Apollo Project; understanding the human genetic makeup would eventually lead to miracle drugs, and one day, the mysteries of the human aging process and illnesses would be unveiled.

When he turned to the second page, Shenzhen News, a bold headline above a half-column story jumped out at him:

HU GUOHAO, CEO OF LANDMARK REALTY, ACCIDENTALLY DROWNS WHILE SWIMMING

Nie’s gaze froze, shocked to read that Landmark Realty’s CEO was dead. He was incredulous, because a mere four days earlier he had interviewed Hu.

Putting down his congee bowl and the newspaper, he waved the waitress over.

“Check, please.”

She handed him his check for 46 yuan, including the tea.

After paying, he left the restaurant and crossed the street to a Friendship Store newspaper kiosk, where he bought several Shenzhen and Guangdong newspapers.

He scanned them for news of Hu’s drowning, and found it under bold headlines:

SHENZHEN BILLIONAIRE HU GUOHAO DIES UNEXPECTEDLY AT LESSER MEISHA BEACH

Was the cause a heart attack?

With Hu Guohao’s death, who will take over Landmark?

Landmark CEO dies at Lesser Meisha, leaving many unanswered questions.

According to one of the papers:

Mr. Zhong, assistant to the CEO of Landmark Realty, confirmed that Hu Guohao, CEO and Chairman of the Board of Landmark Realty, passed away on June 24 at the age of 58. Sources say that Hu drowned while swimming beyond the shark barrier at Lesser Meisha Beach. Experts are trying to determine if it might have been the result of a heart attack. No definitive cause has yet been announced.

Another paper included Hu’s portrait photo; he was dressed in a suit, with closely cropped hair and a radiant smile.

It was a smile tinged with mockery, familiar to Nie Feng. On the morning of June twenty-second, he’d interviewed Hu for three hours and had just finished the article that morning under the title “The Westward Strategy of a Real Estate Tycoon in South China.” Nie could still recall Hu’s ambitious buyout plans, his insightful views on real estate development in western China, as well as the tycoon’s expansive manner. How could such an energetic heavyweight die so suddenly?

On the day of the interview, Hu had commented liberally on a wide range of topics, talking and laughing with confidence. He had no doubts regarding Landmark’s upcoming development in the Yantian seaside district, and although Nie sensed that beneath his expansive demeanor, Hu was feeling either pressure or fatigue, he detected no omens of misfortune.

Why in the world would such an important businessman risk his life by swimming beyond the shark barrier, only to be swallowed up by the waves of Lesser Meisha?

Perhaps owing to his instincts as a journalist, Nie felt that Hu’s death was too sudden.

Even though he’d eaten only half his breakfast, he raced back to his hotel room.

Endless questions flooded his mind as he dialed the number for the CEO’s office.

“Landmark Realty, may I help you?”

It sounded like Ah-ying, Hu’s assistant.

“Hello, this is Nie Feng.”

“Oh, hello.” There was a hint of reluctance in her voice.

“Is the news about Mr. Hu true?” he asked.

“Yes … it’s true.”

“How could he have just drowned?” Nie was puzzled.

“It came as a total shock to us all. It seems that the police…”

Ah-ying sounded evasive, obviously a sign of her own disbelief, but Nie was able to confirm Hu’s death.

“Have the police reached some kind of conclusion yet?” Nie sensed something unusual.

“It seems that…”

She used “it seems” again. Was she puzzled or was there something she could not say?

Since there was no point in continuing, he hung up. After mulling over what to do next, he decided to leave for Shenzhen.

He rang his friend at Zhuhai Publishers.

“Sorry, pal, but something came up and I can’t see you today.”

“What’s so urgent?”

“I’ll tell you later. I can’t talk about it over the phone.”

“It’s a scoop, isn’t it?” His friend had a reporter’s nose.

“Maybe, maybe not. It’s got something to do with my special piece.”

Then he called his editor-in-chief in Chengdu, telling him he’d finished his article late the night before and had already e-mailed it over. Nearly all of Nie Feng’s stories appeared on the first page.

Wu sounded pleased on the phone, as he said brightly, “Perfect! Just in time for the next issue. I’ll treat you to a meal at Lao Ma’s Hot Pot when you return.”

“No need for that, just up my fee for this one,” Nie said half jokingly, recalling how the editorial committee underpaid him each time.

“No problem. This is a special feature, so you’ll get a special fee. Say, when are you coming back?”

“I was going to take the train tomorrow, but something’s come up.”

“What’s that?” Wu’s ears pricked up.

“I’m not sure yet, I’ll let you know tomorrow.”

After hanging up, Nie packed his bag and checked out of the hotel, then took a taxi to the Guangzhou Train Station, where, half an hour later, he boarded T757, a special express train for Shenzhen.

Guangzhong’s gray buildings and undulating highway overpasses flew past his window, and as the train rumbled along, Nie kept thinking back to the interview at Landmark four days earlier.

He remembered every detail about his meeting with Hu. Particularly unforgettable was the luxurious office, which must have occupied at least two hundred square meters. He felt as if he’d entered a palatial hall the moment he stepped into Hu’s office. In the country’s interior, not even a provincial governor could boast such an impressive office.

All the furnishings were of the finest quality, including the carpet, with its auspicious design, and the linen wall hangings.

Hu had sat in his black leather chair behind a massive desk, looking quite poised as the interview began.

Dressed in a dark blue suit, he was tie-less. A bulbous nose and broad, bold face gave him a somewhat aggressive appearance, but he was personable and approachable, quite easygoing, in fact. An enormous photograph of the Landmark Building hung on the wall behind him. Glass cabinets on both sides were filled with trophies and books; a gold-plated pen set, a desk calendar, and a black record-a-phone rested on the desk, in front of which sat a gleaming lifelike black wood carving of an African crocodile, its mouth open wide.

Hu gave a brief account of Landmark’s business ventures and its successes. It had started out as a small real estate company in Hainan, but with tenacity, hard work, bold vision, and an unbending will to win, he had turned it into a megacompany after years of fierce competition. Hu did not bother to conceal his pride when he talked about his rising fortunes in Hainan years before.

“Ten years ago, when I was selling real estate with a friend in Hainan, there were more than fifteen thousand real estate agencies. It was so crowded it felt like a marketplace. If a steamed bun had dropped from the sky, it could easily have killed more than one Realtor.”

Hu, who spoke with a Henan accent, swatted away the imaginary steamed bun with his hand.

“But the number of agencies dropped to a few hundred, and we were one of them. Ha-ha. Luck has been with me.”

As a complacent smile creased the corners of his mouth, Hu exuded a roguish charm.

As for China’s real estate development, he believed that now was the time to move westward. After ten years of large-scale development, China’s real estate market was well organized and ripe for further investment, so it was simply a matter of time before outside developers came in. Whoever moved first would reap the greatest profits. Now there were two keys to success in Western China. The first was capital, the second brand name. Hu then described Landmark’s ambitious acquisition plan; the first step was to acquire land in the Tiandongba area along the shore.

“The value of that land will definitely climb.” A sly glint shone in his beady eyes.

The second step was to move westward. “Didn’t you say there’s no Landmark building in Chengdu? Well, I’ll build a Landmark Building West on Renmin South Road. What do you say to that?”

Witnessing the style and behavior of a true real estate tycoon, Nie Feng realized the importance of bold vision and impressive bearing in the success of a private businessman. It was obvious that Hu was in total control of the conglomerate.

When asked about his hobbies, Hu said he liked to swim and jog, and didn’t play golf.

“That’s a pastime for cultured people.”

As the interview neared its end, Ah-ying came in with a glass of water.

“Chairman Hu, it’s time for your medicine.”

Hu shook out two white tablets from a small bottle on his desk, tossed them into his mouth, took the glass from Ah-ying, and downed the pills.

“Aspirin, a cure for everything,” he said in a self-mocking tone.

“Do you have a cold?” Nie asked.

“No, Mr. Hu has a heart condition,” Ah-ying answered for him.

“The doctor told me I have coronary heart disease. That’s utter nonsense. Do I look like I have a heart problem?”

“No.” Nie said, and meant it.

Copyright © 2016 Song Ying.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Song Ying is an award-winning author in China of both fiction and nonfiction. He has published five bestselling novels and 15 nonfiction books.

The team of HOWARD GOLDBLATT and SYLVIA LI-CHUN LIN have translated the work of virtually all the major Chinese novelists of the post-Mao era—in all more than 50 books. Together they have received three translation awards from the NEA, and a number of prizes. They translated POW! and Sandalwood Death by Mo Yan, who won the 2012 Nobel Prize in Literature